“Adam’s whopping (1.9 kg), wonderful new book.”

“This is a book which warms your heart and allows you to revel in the skill and imagination of one of the great British illustrators.”

“This handsome celebratory book, with a Foreword by Philip Pullman.”

“William Heath Robinson’s lovable illustrations capture the pleasures of a more mechanical age, says Philip Pullman.”

“Book of the Month. This is a brilliantly conceived and executed volume playing homage to the master.”

“This book would be considered a marvel of bookmaking in any age.”

“A delightful visual feast complemented by the author’s enthusiasm for a man who brought warmth to his subjects while giving a discreet two-fingered salute to officialdom.”

“Explores the world of Heath Robinson with an attention to detail and sense of humour fitting for the subject.”

“There was method to the madness of Heath Robinson’s extraordinary illustrations.”

“The author is a well-known television presenter and his pithy comments against each drawing greatly enhance this large volume.”

“Hilarious! Buy it, keep it! Always something new to discover.”

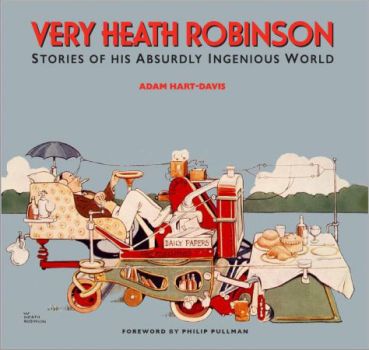

Very Heath Robinson

Stories of His Absurdly Ingenious World

By Adam Hart-Davis, Foreword by Philip Pullman

£40.00

Free delivery on orders over £20

Dispatched in 48 hours with Royal Mail 2nd Class

- RRP: £40.00

- Format: 270 mm x 284 mm (10 ½ x 11 1/5 in) landscape

- Pages: 240

- Weight: 1.9 kg (4 lb)

- Pictures: 350 in colour and b/w

- Binding: Hardback with jacket

- ISBN: 978-1-873329-48-1

- Publication: May 2017

Stories of his Absurdly Ingenious World

‘I have been ill and frightfully bored and the one thing I have wanted is a big album of your absurd beautiful drawings to turn over. You give me a peculiar pleasure of the mind like nothing else in the world.’

– H. G. Wells to W. Heath Robinson (1914)

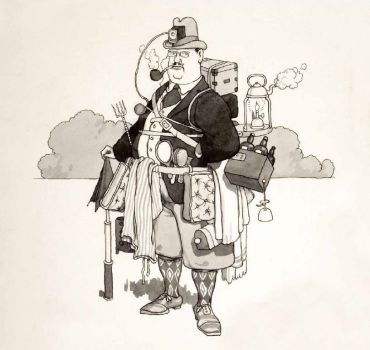

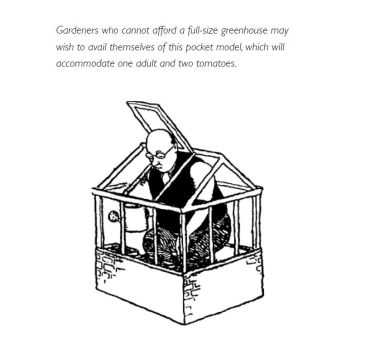

This book takes a nostalgic look back to the imaginative world of William Heath Robinson, one of the few artists to have given his name to the English language. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the expression Heath Robinson is used to describe ‘any absurdly ingenious and impracticable device’. You will find plenty of them here. Very Heath Robinson is full of quirky contraptions for lighting cigars, making coffee, extinguishing candles and generally making everyday life easy. You can even mow the lawn in comfort thanks to the super deluxe Ransomes’ motor mower, complete with wireless, drinks cabinet and tiffin table.

Enthusiastic writers

Adam Hart-Davis is the perfect person to set the artist’s mechanical fantasies in context, to tell the stories of rapid technological and social change that lay behind Heath Robinson’s idiosyncratic brand of satire and to laugh along with the jokes. Known for his popular television series What the Romans Did for Us and other programmes on the history of science and engineering, he is an avid fan of Heath Robinson and full of stories that lie behind the pictures. His love of Heath Robinson is endorsed by Philip Pullman, who conveys the charm of the Heath Robinson repertory company, the earnest, top-hatted men who oversee the machines and are ‘convinced they are being rational and clever and up-to-date’.

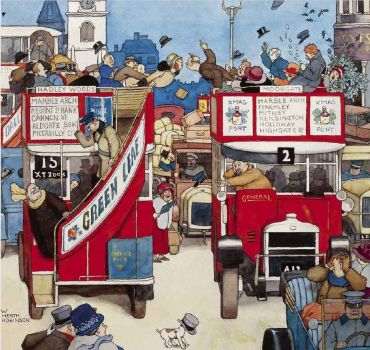

A dozen collections of Heath Robinson’s work have been published over the last 80 years, starting in his lifetime, but most have been compilations of pictures with minimal text. Very Heath Robinson is the first to explain the technical and social background out of which the pictures grew and to weave art and history into a connected story. It portrays Heath Robinson as the visionary he was, foreseeing technical advances decades before they occurred and commenting wryly on urban issues such as traffic jams, litter and flat living that regularly niggle us today.

More articles…

Celebrating 150 Years of Heath Robinson | How Very Heath Robinson! | Pullman Wins J. M. Barrie Award | Philip Pullman Writes on Heath Robinson

FOREWORD BY PHILIP PULLMAN

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER 1: IDEAS FOR DOMESTIC BLISS

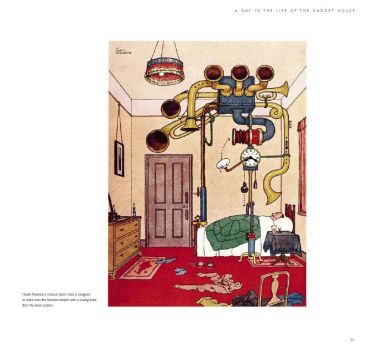

A Day in the Life of the Gadget House

And So to Bed

Close Quarters

Sharing Scarce Facilities

Extending Out

Making the Most of the Garden

CHAPTER 2: KEEPING UP APPEARANCES

Manners Maketh Man

Finer Points of Courtship and Romance

Secret Liaisons

Dressed to Impress

Clothes for Hire

The Body Beautiful

Patent Remedies

CHAPTER 3: HOLIDAYS AND PASTIMES

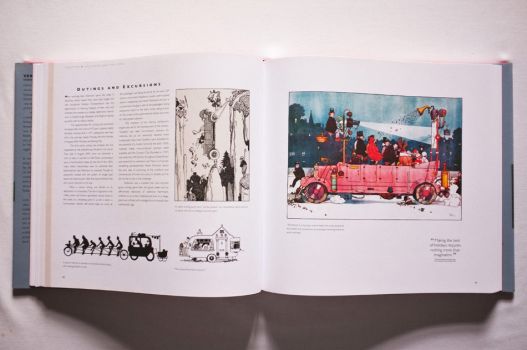

Outings and Excursions

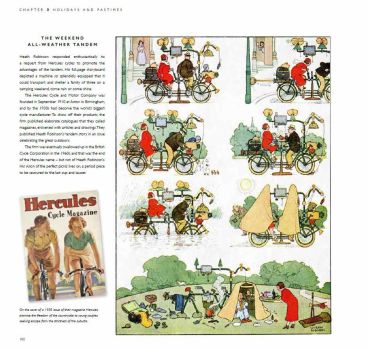

The All-Weather Weekend Tandem

Beside the Seaside

Bathing Belles

Practical Precautions

Tricks of the Camera

Self Photography

Studio Secrets

CHAPTER 4: FOR INSATIABLE SPORT LOVERS

Eye on the Ball

Fast and Slow Cricket

In and Out of the Scrum

The Humours of Golf

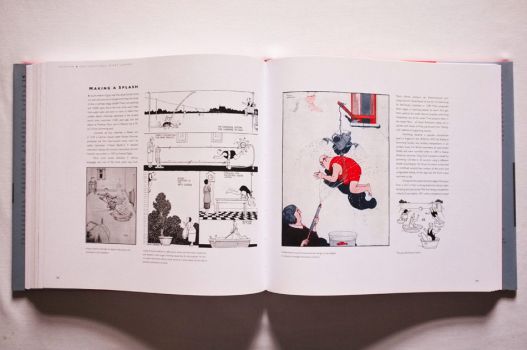

Making a Splash

The Incomplete Angler

Hunting for Cads

Winter Wheezes

Combination Games

CHAPTER 5: MAN AND MACHINE

Mighty Moving Machines

Before It Was Banned

The Pelican in the Factory

Twister!

Heat and Fury

Keeping the Store Cupboards Stocked

From Stone Age to Toffee Town

Cracking on with Christmas

Livening up Left-Overs

Tartan Industries

Testing, Testing

CHAPTER 6: CARS, ‘PLANES AND FLYING TRAINS

Early Days on the Railways

Moving Forward

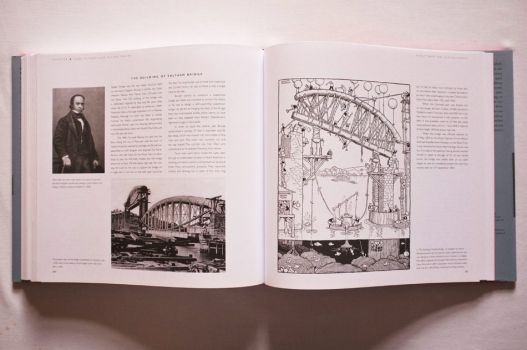

The Building of Saltash Bridge

Ancillary Services

Compartments Galore

Imagining the Channel Tunnel

Manners for Motorists

Safety First

Duck to Water

Running Late

Clearing the Way

Dreams of Aerial Travel

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

PICTURE CREDITS

INDEX

Adam Hart-Davis is the irrepressibly enthusiastic presenter who romps across our television screens bringing excitement to all manner of scientific and technical subjects. Instantly recognizable in his bright and eccentric clothes, he has enlightened his viewers on all manner of topics from the development of nuclear fusion to boiling the perfect egg. He made his name presenting shows such as What the Romans Did for Us and Local Heroes and has a long list of books to his credit, from serious titles like The Cosmos: A Beginner’s Guide and Engineers through to the light-hearted Stringlopedia and Taking the Piss: A Potted History. After attending Eton College, he read chemistry at Merton College, Oxford and did a PhD in organometallic chemistry at the University of York and three years of post-doctoral research at the University of Alberta in Canada. He spent the next five years working at Oxford University Press, where he edited scientific texts and chess manuals. In 1977 he began his career in broadcasting, working for 17 years at Yorkshire Television, first as a researcher and subsequently as producer of series such as Arthur C. Clarke’s World of Strange Powers and the school show Scientific Eye. In the 1990s he presented two series for Yorkshire Television, Local Heroes and On the Edge. Local Heroes proved immensely popular and was moved to BBC2. As well as the Romans, he did programmes on what the Victorians did for us, not to mention the Ancients, the Tudors and the Stuarts. He has collected fourteen honorary doctorates in addition to numerous awards for his services to engineering. He discovered while making a television programme that he is a distant cousin of the Queen, David Cameron and John Julius Norwich.

Adam Hart-Davis is the irrepressibly enthusiastic presenter who romps across our television screens bringing excitement to all manner of scientific and technical subjects. Instantly recognizable in his bright and eccentric clothes, he has enlightened his viewers on all manner of topics from the development of nuclear fusion to boiling the perfect egg. He made his name presenting shows such as What the Romans Did for Us and Local Heroes and has a long list of books to his credit, from serious titles like The Cosmos: A Beginner’s Guide and Engineers through to the light-hearted Stringlopedia and Taking the Piss: A Potted History. After attending Eton College, he read chemistry at Merton College, Oxford and did a PhD in organometallic chemistry at the University of York and three years of post-doctoral research at the University of Alberta in Canada. He spent the next five years working at Oxford University Press, where he edited scientific texts and chess manuals. In 1977 he began his career in broadcasting, working for 17 years at Yorkshire Television, first as a researcher and subsequently as producer of series such as Arthur C. Clarke’s World of Strange Powers and the school show Scientific Eye. In the 1990s he presented two series for Yorkshire Television, Local Heroes and On the Edge. Local Heroes proved immensely popular and was moved to BBC2. As well as the Romans, he did programmes on what the Victorians did for us, not to mention the Ancients, the Tudors and the Stuarts. He has collected fourteen honorary doctorates in addition to numerous awards for his services to engineering. He discovered while making a television programme that he is a distant cousin of the Queen, David Cameron and John Julius Norwich.

Philip Pullman has been named by The Times as one of the ‘50 greatest British writers since 1945’. He is best known for His Dark Materials (1995-2000), a trilogy of novels which has found an audience with adults and children and has sold more than 17.5 million copies worldwide. In 2007 it was made into the blockbuster film The Golden Compass which earned a staggering $150 million, as well as a play at the National Theatre, winner of two Laurence Olivier awards. Northern Lights, the first book in the trilogy, was named the all-time greatest Carnegie Medal winner following voting by both a librarians panel and the public. Dubbed by The Guardian as ‘one of the supreme literary dreamers and magicians of our time’, Pullman has long been an admirer of Heath Robinson’s genius and has expressed his unreserved support for the opening of the Heath Robinson Museum in Pinner. The first volume in his new trilogy The Book of Dust will be published in October 2017.

CHAPTER 1: IDEAS FOR DOMESTIC BLISS

Chapter Opener

This home-made vacuum cleaner bears more than a passing resemblance to James Murray Spangler’s original makeshift invention. As Heath Robinson says, “anyone can make a vacuum cleaner”.

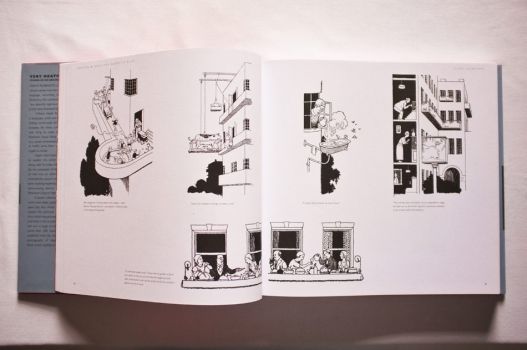

During the 19th century the Industrial Revolution had brought significant changes to Great Britain. The population increased from eight million in 1800 to 30 million in 1900, and these people had to live somewhere. The rapid development of cotton and other mills attracted workers into the towns and cities, and at the same time the modernization of agriculture meant that many fewer labourers were needed on the farms. Before 1800 most people worked in the fields and lived in the country; after 1900 most people worked in industries and lived nearby.

As people migrated into towns and cities, suburbs developed to cope with the influx. Suburban houses were small, and often divided into maisonettes and flats. During the 19th century most better-off families had two or three servants: perhaps a cook, a parlour maid and a butler. The Robinson household, William claimed, included “a general servant, a kitchen maid, a nurse, a housemaid, and a cook; but as all these retainers were united in one person, our household was not greatly increased thereby”.

Aspiring middle-class families did not really have enough money to employ servants, nor space to house them, especially if their new home was less than a complete house. For some, the loss of servants was a dreadful imposition. How could middle-class people be expected to light their own fires, cook their own food and clean their own houses? In addition, how could they possibly live in a small house? Once his imagination got to work, however, Heath Robinson found ingenious solutions to such potential problems.

The advent of domestic gadgets meant that servants were becoming less necessary. Hubert Cecil Booth’s original vacuum cleaner of 1901 was a steam-powered machine the size of a large cart, and pulled by horses. When you summoned it, the monster was brought to the road outside your house, and pipes led in through several windows to bring the vacuum to your carpets and upholstery. This was an important social event, and ladies would invite their friends to come and take tea and observe the wonderful machine in action.

In 1908, James Murray Spangler, a 60-year-old asthmatic janitor in Canton, Ohio, put together a carpet sweeper with a fan and a pillowcase on the back to catch the dust. He could take this portable electric machine round the building with him; it kept the dust down, and reduced his asthma attacks. He took out a patent, and set up the Electric Suction Sweeper Company to make his machines.

William H. Hoover, who made leather horse collars and harnesses, was worried about the threat to his business from the advent of the automobile. He saw one of Spangler’s machines, was immensely impressed and bought the entire business for $36,000. Offering a week’s free home trial, the company was so successful that we still talk about “Hoovering” rather than “Boothing” or “Spanglering”, even though Hoover did not invent the vacuum cleaner.

CHAPTER 3: HOLIDAYS AND PASTIMES

Beside the Seaside

The Robinsons loved trips to the seaside. “As soon as the days grew longer, and summer was in the air, we began to look forward to our seaside holiday, which we usually spent at Ramsgate…. The entertainments on the sands were of a simple character. We had no fun-fairs, great wheels, or other Blackpool thrills. We had no concert parties, but were sufficiently amused… by Punch and Judy. The photographer, too, was always busy with his little portable darkroom.”

The seaside had long been associated with health as well as pleasure. The fresh air, sunshine and sea-water were all considered beneficial to the constitution. In his 1769 book Domestic Medicine, the Scottish doctor William Buchan recommended sea bathing, especially during winter – not for fun, but as a cure for various diseases. The lower the temperature, the more beneficial the effect. Since the book sold 80,000 copies he must have persuaded many people to try it. Heath Robinson was clearly less than enthusiastic, for his drawings show a range of tactics to avoid hypothermia. Others said that immersion in water caused lascivious thoughts, disgraceful behaviour and moral turpitude.

The idea that sea air was good for you became popular after the discovery of the gas ozone in 1839. When passing an electric current through water to separate the oxygen from the hydrogen, the German scientist Christian Friedrich Schönbein noticed a distinctive odour, identified the gas and named it ozone, from the Ancient Greek ὀξειν, to smell. Ozone turned out to be a powerful antiseptic, so it came to be associated with hospitals and doctors’ surgeries. Since people thought they could catch a whiff of it at the seaside, they assumed that sea air had to be beneficial. In fact ozone is antiseptic because it is a deadly poison; one good breath and you’d be dead. Fortunately there is no ozone at the seaside; the characteristic smell is actually rotting seaweed. That did not deter the Victorians from developing seaside resorts all around the coastline, many of them equipped with piers so that people could walk out over the sea and breathe the healthy air.

Bathing Belles

In Victorian times men and women would rarely swim from the same beaches and women wore enormous, all-concealing bathing costumes. Bathing machines first appeared at Scarborough in 1736. These were wooden huts or canvas tents on wheels in which people could change out of their clothes. The machine could then be taken down to the water’s edge so that the bathers could leap in without exposing themselves. Some machines even went right into the sea to allow the bathers to immerse themselves in total privacy. Queen Victoria had a bathing machine installed in 1846 at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight and used it the following year.

In 1907 the Australian swimmer Annette Kellermann was arrested on a beach in Boston for wearing a figure-hugging costume, even though it covered her from neck to ankle. Heath Robinson shows some women in cover-all outfits, but in other pictures has men and scantily-clad women cavorting together. Gradually, costumes became slighter, and some of Heath Robinson’s later drawings show women in skinny one-piece outfits. The bikini was not “invented” until 1946, when the French designer Jacques Heim produced the “Atome”, the smallest bathing suit in the world, whereupon his rival Louis Réard produced an even smaller one and – anticipating its explosive impact – named it the “Bikini” after Bikini Atoll, where the Americans had just tested the world’s first hydrogen bomb.

CHAPTER 6: CARS, ‘PLANES AND FLYING TRAINS

Chapter Opener

Heath Robinson lived through an era of unprecedented progress in transport. Railways had already revolutionized travel in the mid-19th century, and the network went on growing in the 1900s. The first cars and motor buses appeared in the 1890s. Travel across seas was greatly improved by the invention of the steam turbine by Charles Parsons in 1897, which gave rise to a new generation of fast steamships. Most important of all was the development of passenger aircraft after Orville and Wilbur Wright made the first controlled, powered flight in a heavier-than-air machine in 1903. New and more advanced models were being introduced up to and throughout both world wars.

The world’s first dedicated passenger train ran from Liverpool to Manchester on 15th September 1830. The day was a triumph for the engineer George Stephenson and the locomotive Rocket, built by his son Robert. It was also a tragedy for the M. P. William Huskisson, who rashly crossed the line to talk to the Duke of Wellington, was run over by Rocket and died from his injuries.

The merchant venturers of Bristol observed Stephenson’s work with trepidation. They worried that a railway connection with London might make Liverpool a more important port than Bristol, and decided they needed a railway of their own; so in 1833 they formed the Great Western Railway company or G. W. R. – sometimes known as God’s Wonderful Railway – which received its enabling Act of Parliament in 1835.

To build the railway, the merchants turned to 21-year-old Isambard Kingdom Brunel, who had spent a year in Bristol recovering from an accident in the Thames Tunnel in 1828, and had made major improvements to the docks there. They told him at an interview that they were going to ask four engineers each to survey a route for the railway, and would choose the cheapest.

Brunel, already arrogant in spite of his youth, said that under those conditions he was no longer interested. If he were to survey a route, it would be the best route, but certainly not the cheapest. And he walked out. A fierce argument ensued, and the merchants decided by a single vote to give Brunel the job. This was by far his biggest project and, refusing to delegate, he surveyed every yard of the route himself, and even went so far as to design the lamp posts for Bath railway station.

By the end of the 19th century, most major cities were linked to the rail network, although in London the railway companies were not allowed to carry their noise and smoke into the centre; so the stations lie mainly in two rows, north and south of the centre. Once the train had brought you to your destination, therefore, there was urban traffic to contend with – already a problem long before the advent of the internal combustion engine.

In the 1890s, when Heath Robinson was in his 20s, manure was a nightmare. London had 11,000 cabs and several thousand buses, pulled by a total of 50,000 horses. Each horse produced 20 pounds of manure per day; New York had 2.5 million pounds per day to shift. In 1894, The Times of London predicted that by 1950 the city’s streets would be buried under nine feet of manure. So serious was the problem that an international urban planning conference was held in New York in 1898 to discuss the issue, but since none of the delegates could see any solution, they gave up after three days and went home. Yet within a few years the problem had entirely disappeared. Electric trams and then cars and motor buses led to a rapid collapse in the horse population; in 1912, traffic counts in New York, London and Paris all showed more cars than horses for the first time, and most cities had experienced their first motor traffic jams by 1914.

These new and exciting developments in transport inspired Heath Robinson’s own idiosyncratic view of how trains, ships, motor cars and ’planes operated – a cornucopia of churning pistons, tooting whistles and smoke-billowing engines.